Fictional scenario - it's Monday morning and my team is paged.

The new feature we put live last week is broken in production. Customers are annoyed. Support is asking when a fix can be expected.

Logs don't tell us much. Traces are minimal. Three databases to check... and no idea where to start looking.

By the time there's an outage, it's too late. We're scrambling, guessing, and burning time.

Observability-driven development from Charity Majors has changed the way I build software.

My normal workflow used to be build, deploy, then tack on observability as an afterthought.

In ODD, I build observability into the codebase as I go and validate my code behaves as I expect in production.

Only then do I declare the feature done.

Example - CRM Sync

A few years ago I built a small piece of software to sync contacts between a CRM and an email newsletter.

We deployed, monitored for errors, everything seemed fine. Six months later, the client discovered that 17% of contacts weren't syncing.

The system was silently losing data. Contacts weren't flowing, leads weren't getting emails. Nobody knew.

I recently worked with a client who needed a similar CRM integration.

I'd learned my lesson. This time I built with Observability Driven Development.

Principles

Some ideas behind Observability Driven Development:

- Embrace failure

- Instrument incrementally

- Close the loop

1. Embrace failure

I can't predict all the ways my code will break in production. Yes, I still try. Yes, I write extensive unit tests. But with complex distributed systems, there will always be strange behaviour in production.

Unit tests in the sandbox of my local laptop catch so many bugs.

However, software in the wild will always fail in new, interesting and unpredictable ways.

Instead of asking "Will this code work in production?", I ask "How will I know if this code breaks in production?".

2. Instrument incrementally

I wouldn't merge a pull request without tests. So I don't merge a pull request without instrumentation.

I add a small slice of observability alongside every feature I ship. Just like tests and documentation.

This small slice of observability helps me understand the question posed in step 1: "How will I know if this code breaks in production?".

3. Close the loop

After I deploy, I fire up my observability tool and query the data generated.

Is the code running? Are customers using it? Does the feature behave as expected? Does anything look weird?

I poke around and get curious. If I see something unexpected, I drill down, fix the problem, deploy and repeat.

I only declare the feature done when I can see the feature actually working in production.

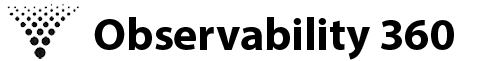

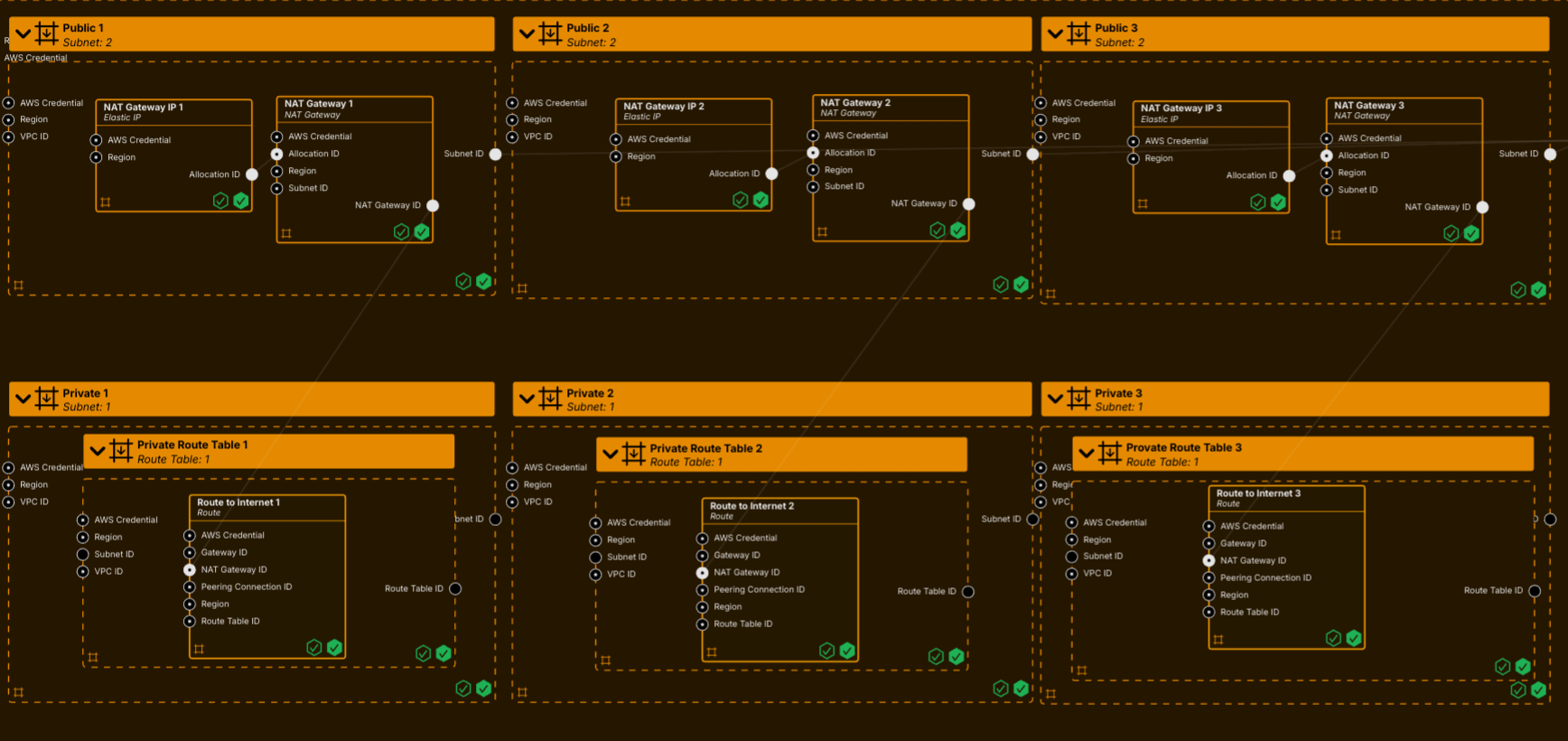

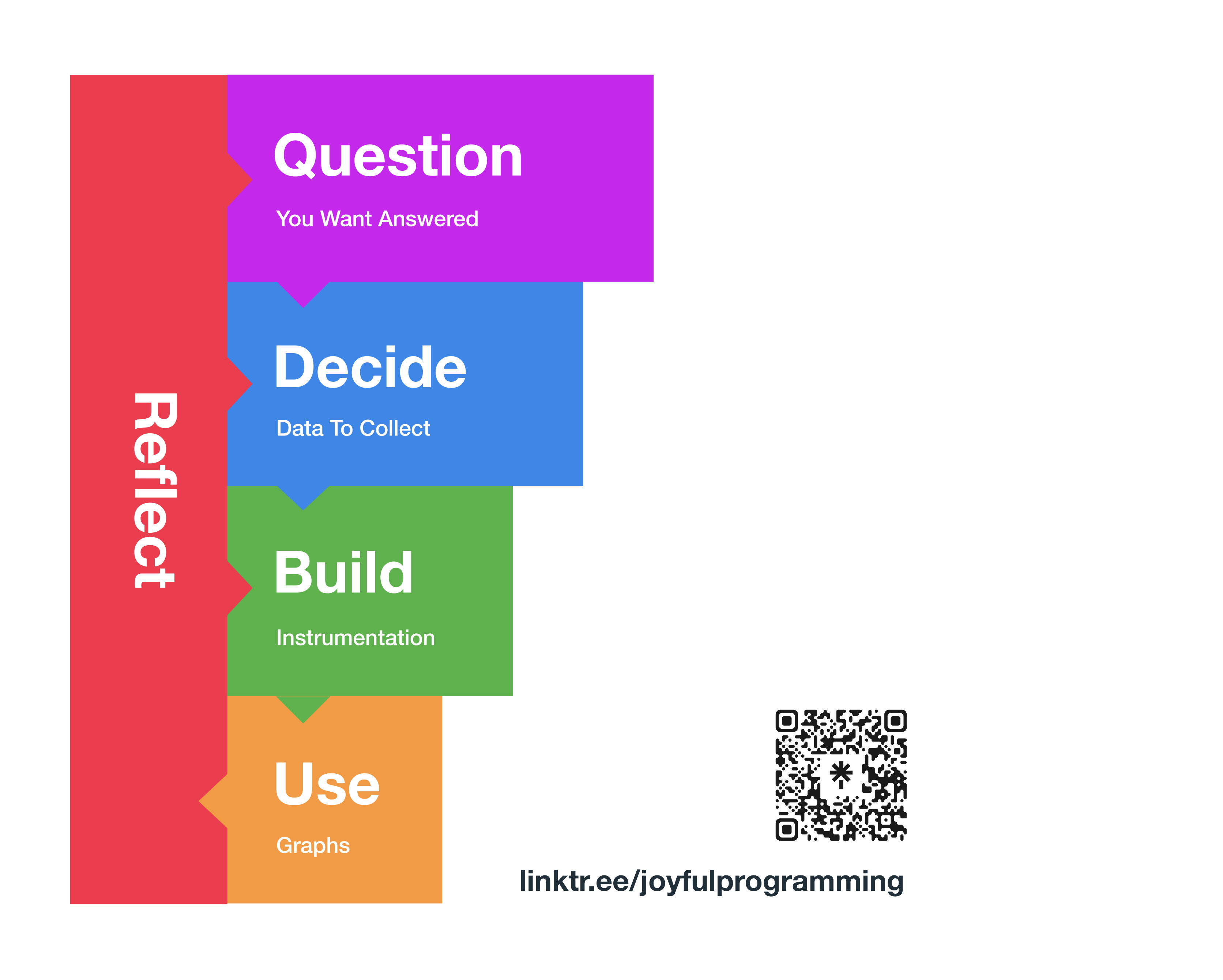

Steps to Observable Software

To give us structure around these principles, I've come up with a five step process.

The five steps are:

- Question - Form the question are you trying to answer.

- Decide Data - Decide on which data is needed to answer the question.

- Build - Write code to instrument your app and collect the data.

- Use - Use your observability tool - logs, traces, metrics - to try to answer the question.

- Reflect - What happened? Did you answer the question successfully? Or was there not enough data? Or is a change in direction needed? Return to the relevant step.

Worked Example

Let's see exactly how this works with the CRM sync example.

Step 1: Question

We want a fitness function for the feature.

How do I know if this feature is delivering value?

How will I know if the code is working?

I came up with three questions:

Question 1: What percentage of contacts have been successfully synced? (Is the feature working correctly?)

Question 2: How long does it take for each contact to sync? (Is the feature too slow?)

Question 3: How many contacts are being synced an hour? (Is the feature being used by customers?)

Step 2: Decide Data

When deciding on the data to collect, I break down each question into four dimensions:

A. Event - what event that happened in the past are we measuring?

B. Filter - what attributes are we filtering by?

C. Group by - what attributes are we grouping by?

D. Values - what values are we plotting?

Let's do this for each question.

A. Event - HTTP Request Sent

B. Filter - URL = "https://mailing.list/api/contacts" AND Method == POST

C. Group By - Status Code

D. Values - N/A

A. Event - Contact Synced

B. Filter - N/A

C. Group By - N/A

D. Values - P95(duration)

A. Event - Contact Synced

B. Filter - N/A

C. Group By - N/A

D. Values - COUNT

All Data Required

Summarising all this, we need:

Step 3: Build Instrumentation

I implemented the business logic for the feature using TDD:

class SyncContact

def call(contact)

# ... business logic here ...

# Faraday is an HTTP client for Ruby

client = Faraday.new("https://mailing.list") do |conn|

conn.adapter Faraday.default_adapter

end

client.post("/api/contacts", contact)

end

end

First event needed is "HTTP Request Sent".

Attributes needed are URL, Method, Status Code and Duration.

Wrote a failing test:

class TestInstrumentationMiddleware < Minitest::Test

def test_records_http_request_sent_event

logs = capture_logs do

SyncContact.new.call(contact)

end

log = logs.find { |msg| msg["event.name"] == "http.request.sent" }

assert_equal "https://mailing.list/api/contacts", log["http.request.url"]

assert_equal "post", log["http.request.method"]

assert_equal 200, log["http.response.status"]

assert_kind_of Numeric, log["http.response.duration"]

end

end

Wrote the implementation:

class SyncContact

def call(contact)

# ... business logic here ...

client = Faraday.new("https://mailing.list") do |conn|

+ conn.use(InstrumentationMiddleware.new)

conn.adapter Faraday.default_adapter

end

client.post("/api/contacts", contact)

end

+ class InstrumentationMiddleware < Faraday::Middleware

+ def call(env)

+ @app.call(request).on_complete do |response|

+ logger.info(

+ "Request to #{request[:url]} completed with status code #{response[:status]} and duration #{response[:duration_ms]}ms",

+ "event.name" => "http.request.sent", # <== HTTP Request Sent Event

+ "http.request.url" => request[:url], # <== URL

+ "http.request.method" => request[:method], # <== Method

+ "http.response.status" => response[:status] # <== Status Code

+ )

+ end

+ end

end

end

Test passes.

Next event needed is "Contact Synced".

Wrote a failing test:

class TestContactSyncedEvent < Minitest::Test

def test_records_contact_synced_event

logs = capture_logs do

SyncContact.new.call(contact)

end

log = logs.find { |msg| msg["event.name"] == "app.contact.synced" }

assert_kind_of Numeric, log["duration"]

end

end

Wrote the implementation:

class SyncContact

def call(contact)

+ start_time = Time.now.to_i

# ... business logic here ...

client = Faraday.new("https://mailing.list") do |conn|

conn.use(InstrumentationMiddleware.new)

conn.adapter Faraday.default_adapter

end

client.post("/api/contacts", contact)

+ logger.info(

+ "Contact synced",

+ "event.name" => "app.contact.synced", # <== Contact Synced Event

+ "duration" => Time.now - start_time, # <== Duration

+ )

end

class InstrumentationMiddleware < Faraday::Middleware

def call(env)

@app.call(request).on_complete do |response|

logger.info(

"Request to #{request[:url]} completed with status code #{response[:status]} and duration #{response[:duration_ms]}ms",

"event.name" => "http.request.sent",

"http.request.url" => request[:url],

"http.request.method" => request[:method],

"http.response.status" => response[:status]

)

end

end

end

end

Test passes.

Gathered the data. Deployed. Time to query the data.

Step 4: Use

After deploying, I queried the logs and created some graphs.

My answers:

- Q1: What percentage of contacts have been successfully synced? - 93%

- Q2: How long does it take for each contact to sync? - P95 of duration is 1.3 seconds

- Q3: How many contacts are being synced a hour? - ~10-50

Step 5: Reflect

Finally, I reflect on the results.

Answer 1 is concerning!

Why are 100% of contacts not being successfully synced?

Looks weird. Let's go back to step 1 and form a new question.

Cycle 2 and Beyond

After a few more cycles, here's what I discovered:

- 7% of contacts were failing to sync

- These contacts were already unsubscribed in the mailing list software

- The HTTP status code was 400 but the code was failing silently

I wrote a failing test fot the defect, fixed the code, deployed.

The percentage of contacts successfully synced increased to 100%.

Everything else looked good.

Finally, I had confidence my code worked in production and I declared the feature done.

Using ODD and this iterative five step process, I've discovered errors, bugs, strange race conditions, upstream issues and much more, all whilst the feature is fresh in my head and I can fix issues immediately.

Action: Build Your Next Feature With ODD

Pick one feature you're building this week. Instead of treating deployed code as done, build with ODD.

Follow the five steps:

Step 1: Question: Create questions that define a fitness function for this feature.

Step 2: Decide: Choose data to answer these questions.

Step 3: Build: Build instrumentation alongside each slice of value.

Step 4: Use: Query the instrumentation once you've deployed.

Step 5: Reflect: What's the answer? Do you need more data? Better instrumentation? Or is there a new question?

Free course offer

John is currently offering a course to teach engineers observability.

- First module is FREE

- Practical and hands on - minimal theory

- Fix a real defect in a real app

- Using Ruby on Rails, but little coding knowledge required

- Takes 2-3 hours

Find out more