eBPF is an overnight success which has been a long time in the making. As last year's Unlocking The Kernel documentary showed, the eBPF interpreter was first merged into the Linux network stack back in 2014. In recent years Isovalent have been at the forefront of bringing the technology to a wider audience - particularly through developing cutting edge open source products such as Cilium and Tetragon.

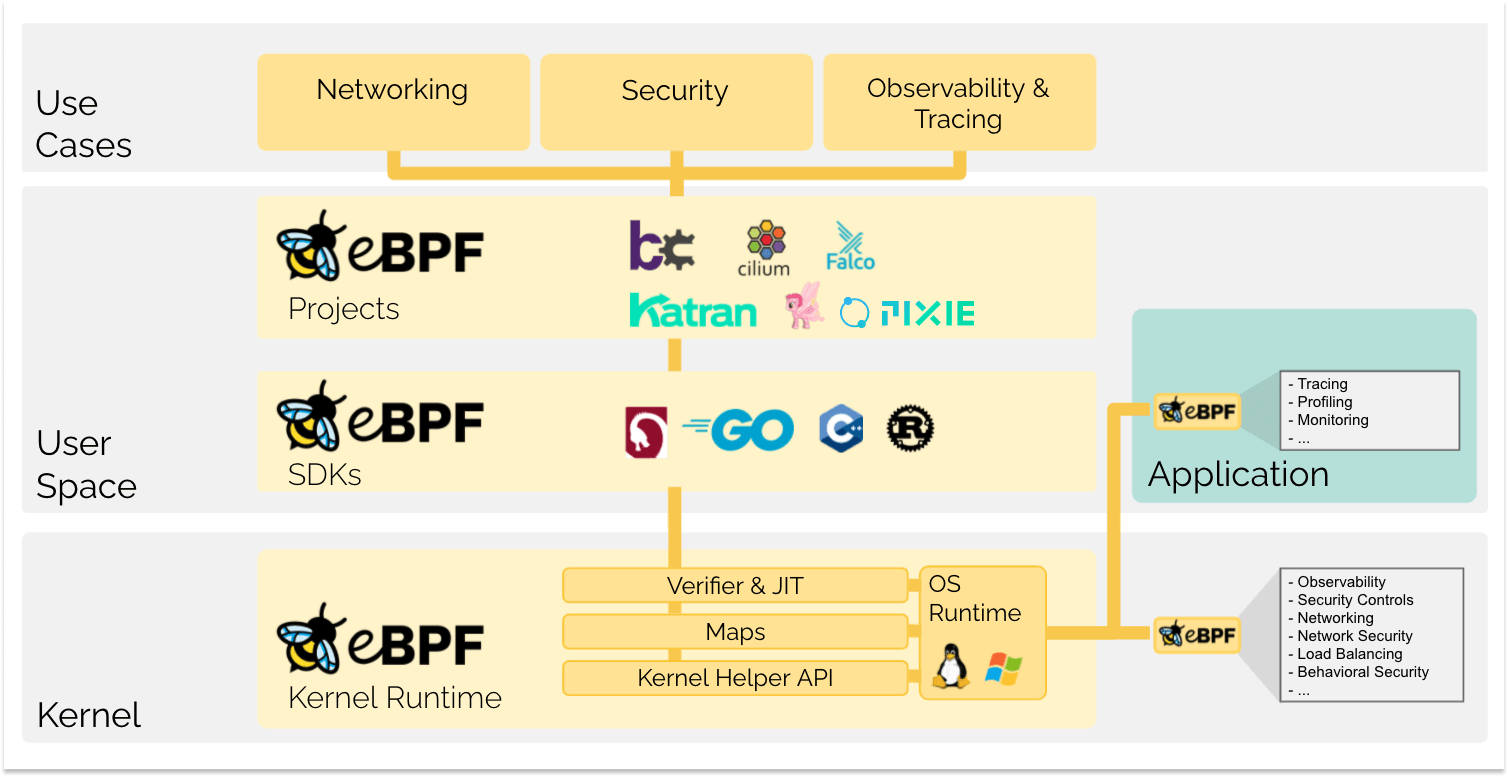

eBPF is a game-changer as it allows applications to hook right in to the Linux Kernel. This means that eBPF applications have clear visibility of network traffic as well as a small footprint and massive scalability. The potential for observability platforms is huge, as applications can attach to the kernel without the need for any kind of user instrumentation.

In this round-up we will look at how a number of leading observability platforms are leveraging the power of eBPF in their tooling. What is striking is that many of the early adopters of eBPF are relative newcomers to the observability market. Clearly, newer stacks, which do not have an existing codebase to re-engineer, are much better placed to embrace this new technology than existing vendors - especially those with a large code-bases and complex architectures.

So, we know that eBPF is a powerful and revolutionary technology - but what are the actual advantages to using it in observability platforms? One of the first advantages of eBPF is that it is open source. It is a building block for observability tooling that does not involve any licensing costs. As such it considerably lowers the barrier to entry for new entrants into the observability space. It is interesting to note, also, that all of the products listed in this round-up are OSS.

Secondly, eBPF (theoretically) obviates the need to develop client SDK's. This can be seen as a win for users as well as for vendors. Developing SDK's compatible with multiple languages, platforms and versions requires significant amounts of effort and finance for vendors. For end users the on-boarding process becomes more frictionless, as cloud-native services no longer need to be instrumented. Thirdly, eBPF applications are faster, more scalable and have a smaller resource footprint than SDK-based solutions

As we know though, every technical decision implies some kind of trade-offs, and eBPF is no exception to this rule. There are a few limitations and considerations to bear in mind.

The first is that, at the moment, eBPF is a Linux-only technology. It is not cross-platform - although a Windows version is under development. Many eBPF solutions are described as being 'cloud-native' - which often boils down to running on Kubernetes - which obviously, in turn, means running on Linux hosts. Many of the eBPF-based systems on the market assume that you are running your services in a K8S cluster. If you are using a different platform then they may not be the right fit. If you are running on a Windows network then the current generation of eBPF solutions simply won't work.

In a similar vein, eBPF solutions will not be able to hook into serverless technologies such as Azure Functions or AWS Lambdas as you do not have access to load the solution into the Linux kernel in a serverless environment. The same limitation applies to technologies such as Azure Web apps or AWS Elastic Beanstalk. Whilst this is by no means a showstopper, it does mean that companies using these technologies will need a solution that supports ingesting telemetry both via eBPF as well as via an agent or a pipeline.

Thirdly, there are, at present, functional limitations to eBPF observability. eBPF is powerful but it is not a magic wand. Whilst eBPF is a fantastic enabler, it takes a large degree of specialist engineering skill and knowledge to craft robust, performant and highly scalable eBPF programs. Not all eBPF programs are made equal. Some will only cover a small subset of languages whilst others may only have partial or incomplete capabilities in capturing logs metrics and traces.

Having looked at some of the general principles and theory of eBPF it's time to start looking at how some leading observability solutions are leveraging its power. In Part One of this article we will look at Pixie - a pioneer for eBPF in obervability. In Part Two, we will survey a number of the other leading products in the market.

It would be somewhat remiss of us if we did not kick off this round-up with Pixie - as far as we know, the first tool the utilise eBPF in observability tooling. Pixie is an open source project which was contributed to the CNCF by New Relic as far back as 2021 and indeed, the project still integrates closely with New Relic. Like most eBPF-based tools, Pixie sets up eBPF probes to trigger on a number of kernel or user-space events.

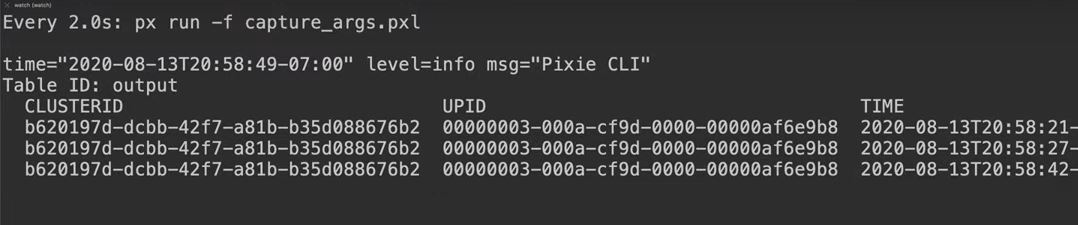

When Pixie is deployed in a K8S cluster, it deploys eBPF kernel probes (kprobes) that are set up to trigger on Linux syscalls used for networking. Then, when your application makes network-related syscalls -- such as send() and recv() -- Pixie's eBPF probes snoop the data and send it to the Pixie Edge Module (PEM).

In the PEM, the data is parsed according the detected protocol and stored for querying. This is encapsulated in the diagram below:

Conceptually, the idea of 'hooking into kernel processes' has quite a simple ring to it. The practical application for observability systems though, entails considerable technical complexity. Complete stack traces are not just sitting around in a neat little box waiting to be collected.

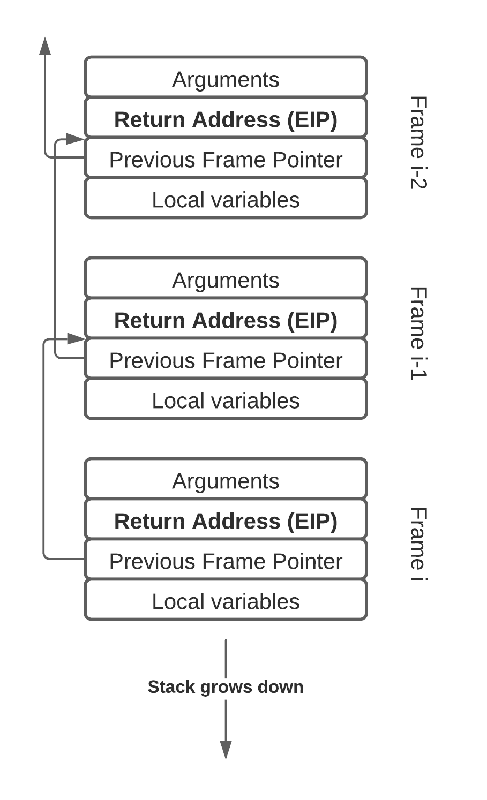

In Pixie, the stack trace is recovered by looking at the instruction pointer of the application on the CPU, and then inspecting the stack to find the instruction pointers of all the parent functions (frames) as well. Walking the stack to reconstruct a stack trace has some complexities, but the basic case is shown below.

One starts at the leaf frame, and uses frame pointers to successively find the next parent frame. Each stack frame contains a return address instruction pointer which is recorded to construct the entire stack trace.

This is a tremendous example of the power of eBPF. In part two of this article, we will continue our round-up by looking at the implementation of eBPF in a further five major systems: